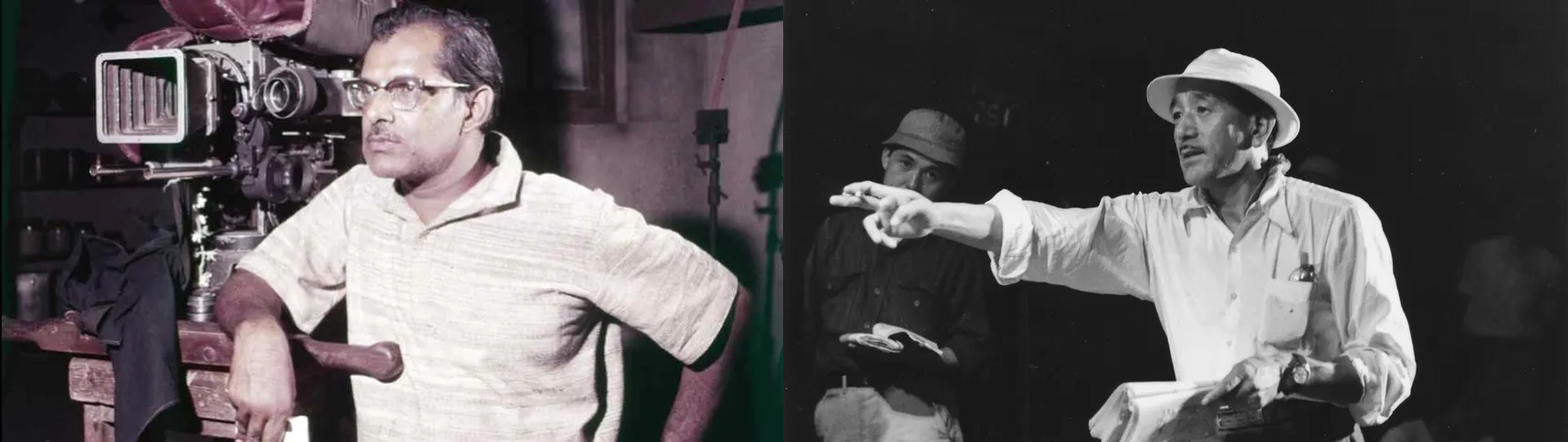

Cinema has the power to transcend borders, cultures, and languages, yet some filmmakers, despite working in entirely different film industries, share a strikingly similar vision. Yasujirō Ozu, the master of Japanese cinema, and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, the beloved storyteller of Indian cinema, may have worked thousands of miles apart, but their films echo the same humanistic essence. Both directors captured the subtleties of middle-class life with warmth, humor, and poignancy, leaving behind cinematic legacies that continue to resonate.

Family and the Middle-Class Ethos

Ozu and Mukherjee were both deeply fascinated by the rhythms of everyday family life. Their films frequently revolved around the joys, struggles, and transitions within middle-class households. Ozu’s masterpieces such as Tokyo Story (1953) and Late Spring (1949) explored generational conflicts and the inevitable passage of time, particularly focusing on the loneliness of aging parents and the quiet sacrifices of children.

Mukherjee, through films like Anand (1971), Bawarchi (1972), and Gol Maal (1979), delved into family relationships, often emphasizing the importance of values, humility, and human connection. Both filmmakers painted portraits of ordinary people caught in the ebb and flow of life, making their cinema universally relatable.

Minimalism and Subtle Storytelling

Ozu was renowned for his minimalistic storytelling—his restrained narratives, static low-angle shots, and careful compositions created an intimate atmosphere. Mukherjee, though not as formally minimalist, also avoided melodrama, favoring gentle, fluid storytelling that let emotions unfold naturally. Neither director relied on exaggerated conflicts; instead, they found drama in the mundane, proving that simplicity can be deeply profound.

Also, both Ozu and Mukherjee mastered the art of blending humor with poignant storytelling. Ozu’s films contained understated, dry humor embedded in everyday conversations, adding levity to otherwise melancholic themes. Good Morning (1959) is a prime example, using children’s rebellion against silence to poke fun at changing societal values.

Mukherjee, on the other hand, used humor in a more pronounced way. His films like Chupke Chupke (1975) and Gol Maal (1979) infused lighthearted comedy while still reflecting on middle-class struggles and values. While their approaches varied, both directors used humor as a tool to enhance rather than overshadow the depth of their narratives.

Strong Yet Ordinary Female Protagonists

Women in both Ozu and Mukherjee’s films were often the emotional anchors of the family. Ozu’s Late Spring (1949) presented the poignant tale of a daughter who sacrifices her happiness for her father, showcasing the quiet endurance of women in traditional Japanese society.

Mukherjee’s Mili (1975) and Abhimaan (1973) featured strong female protagonists who navigated complex emotional landscapes, standing as pillars of strength in their relationships. Both directors portrayed women with nuance, neither idealizing nor diminishing their struggles.

Bittersweet Yet Hopeful Endings

A defining trait of both directors was their ability to craft endings that were emotionally satisfying yet tinged with melancholy. Ozu’s films often concluded with a quiet acceptance of life’s changes, leaving the audience in contemplation. An Autumn Afternoon (1962) ends with an aging father drinking alone, accepting his daughter’s departure into married life.

Mukherjee’s films, such as Anand, concluded on a deeply emotional yet uplifting note, reminding viewers of the transient nature of life but also its beauty. Both directors rejected melodramatic finales, favoring gentle, reflective conclusions that lingered long after the credits rolled.

The Legacy of Two Masters

Though separated by geography, language, and cultural contexts, Yasujirō Ozu and Hrishikesh Mukherjee crafted deeply humanistic cinema that transcended barriers. Their films continue to be celebrated for their simplicity, emotional depth, and profound understanding of human nature. Whether in the quiet corridors of a Japanese home or the bustling streets of middle-class India, their cinema reminds us of the beauty in ordinary life.

In an era of grand spectacles and high-concept storytelling, the works of Ozu and Mukherjee remain timeless, proving that sometimes, the most powerful stories are the simplest ones.

If you have any questions regarding Ozu or Mukherjee, feel free to ask in the comments below. For more content, stay tuned. As usual, like, subscribe and share our articles as we here are trying to build a community of people High on Cinema!